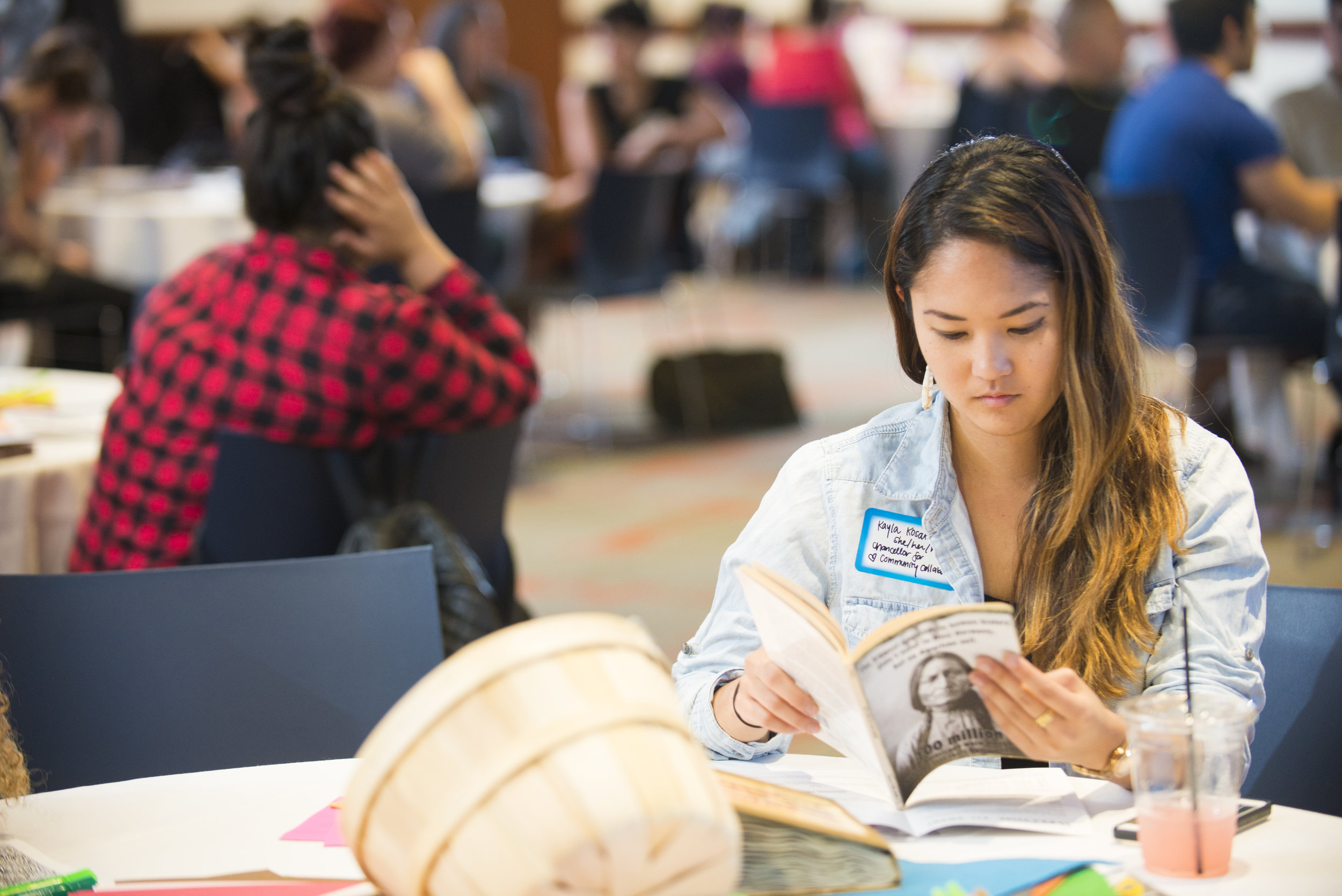

The Des Moines Story Circles began with Emmett emceeing, young people performing poems, and a handful of individual stories presented onstage before sharing began at small tables all around the room. I asked Emmett why they chose to start out this way. “One, to break the ice for everyone, since it’s kind of a new experience just sharing stories. And two, to make sure that the groups that really needed to be included in the conversation got their perspective out first and foremost. We thought it would empower everyone else to be open with what they’ve been through.”

And the poetry? “I work with an organization called Run DSM that has a program called Movement 515 about the urban arts: poetry, graffiti, hip-hop, photography. I’ve done a hip-hop camp and currently do poetry workshops in the middle school with them. They have a lot of young people that are brought up and empowered and trained and rehearsed with poetry. They understand the power in it, and always do a great job. So I reached out to a couple of their poets to come and bless us. We had three different poetic performances, one for the opening and two to close the show.”

I asked Emmett about success factors. “We had great support from the venue. They were courteous. They were there to help us set things up. So the environment definitely played its part. A lot of the people were there off of respect of the people that invited them. It really helps to have like a team where people would follow them wherever they go because they know it’s going to be something good. Starting with poetry was good: a poem from a young high schooler that was very awake and very appropriate, that hit people in their feelings, the emotional investment that says why we’re even here. And the stories had people in tears. A note we took on ways to make the event better is to have more Kleenex handy.”

This year as in previous years, we’ve heard from many participants that Story Circles offer a powerful and simple way to connect people, even those who seem to have little in common. In a Story Circle everyone gets equal uninterrupted time to share a first-person story, usually two or three minutes apiece. Listeners give each teller undivided attention, allowing a breath after each story for it to settle. Those factors often have a large impact in equalizing participation; contrast this to a free-for-all where the loudest or most powerful person hogs the space. After everyone has shared a story, the members of each Circle reflect on what has been revealed by the body of stories.

In Des Moines, once folks in Story Circles started reflecting, it was hard to stop. “Our intention was to have people break into their groups for a little while, then hear from everyone and then do closing poetry. But people were having too much good topical conversation. I just couldn’t stop that. So we let them continue pretty much until we had to leave. People felt really, really open and connected. The event was two hours—it’s crazy that that wasn’t long enough, you know?”

Emmett and his collaborators sent a follow-up question to everyone who took part. A large portion of the participants responded. Forty-two indicated that they’d like to participate in future Story Circles. No one replied to that question with a “no.” The typical response was what we’ve come to expect from PSOTU participants: “Great start. Loved the conversations. Stories need to be told.”

Why is the simple invitation to sit in circles, share stories, and listen fully so powerful? Based on the hundreds of Story Circles I’ve observed and facilitated, two main answers come to mind. First, it can be a sadly rare and remarkably delicious experience to receive full attention, to inhabit the space to tell a story without fearing interruption or contradiction. Too often, people are texting while you talk, or waiting for your mouth to stop moving so their turn can start, or looking over your shoulder for someone they’d rather engage. But the attention and permission of a Story Circle are an antidote to that.

Second, as we say when each PSOTU launches, “Democracy is a conversation, not a monologue.” Too much ordinary public discourse is left to those deemed experts. Too much is conducted in a way that privileges certain types of knowledge—official findings, numbers, the jargon of a particular sphere. What tends to emerge is opinion, and opinion can always be contested. In a polarized moment, many people are made anxious or fatigued by the prospect of a shouting-match fueled by conflicting opinions that fail to persuade. But stories are different. When someone’s first words are, “I want to tell you a story about something that happened to me,” when the sentences that follow tell an actual story, with a beginning, middle, and end, surprisingly few even try to contradict another’s actual experience. Each storyteller’s truth emerges to stand alongside the rest, and when the group reflects on what has been learned, the richness is often unexpectedly powerful.

You don’t have to wait till PSOTU 2018 to try it out. The USDAC’s next National Action, #RevolutionOfValues, is a day of creative action taking place on April, the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King’s groundbreaking Riverside speech. There are many ways for individuals and groups to take part. Download the free Toolkit and you’ll have access to all kinds of resource, including detailed Story Circle instructions.